2019-02-08

Python for Reverse Engineering #1: ELF Binaries

Building your own disassembly tooling for — that’s right — fun and profit

While solving complex reversing challenges, we often use established tools like radare2 or IDA for disassembling and debugging. But there are times when you need to dig in a little deeper and understand how things work under the hood.

Rolling your own disassembly scripts can be immensely helpful when it comes to automating certain processes, and eventually build your own homebrew reversing toolchain of sorts. At least, that’s what I’m attempting anyway.

Setup

As the title suggests, you’re going to need a Python 3 interpreter before anything else. Once you’ve confirmed beyond reasonable doubt that you do, in fact, have a Python 3 interpreter installed on your system, run

$ pip install capstone pyelftools

where capstone is the disassembly engine we’ll be scripting with and pyelftools to help parse ELF files.

With that out of the way, let’s start with an example of a basic reversing challenge.

/* chall.c */

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

int main() {

char *pw = malloc(9);

pw[0] = 'a';

for(int i = 1; i <= 8; i++){

pw[i] = pw[i - 1] + 1;

}

pw[9] = '\0';

char *in = malloc(10);

printf("password: ");

fgets(in, 10, stdin); // 'abcdefghi'

if(strcmp(in, pw) == 0) {

printf("haha yes!\n");

}

else {

printf("nah dude\n");

}

}

Compile it with GCC/Clang:

$ gcc chall.c -o chall.elf

Scripting

For starters, let’s look at the different sections present in the binary.

# sections.py

from elftools.elf.elffile import ELFFile

with open('./chall.elf', 'rb') as f:

e = ELFFile(f)

for section in e.iter_sections():

print(hex(section['sh_addr']), section.name)

This script iterates through all the sections and also shows us where it’s loaded. This will be pretty useful later. Running it gives us

› python sections.py

0x238 .interp

0x254 .note.ABI-tag

0x274 .note.gnu.build-id

0x298 .gnu.hash

0x2c0 .dynsym

0x3e0 .dynstr

0x484 .gnu.version

0x4a0 .gnu.version_r

0x4c0 .rela.dyn

0x598 .rela.plt

0x610 .init

0x630 .plt

0x690 .plt.got

0x6a0 .text

0x8f4 .fini

0x900 .rodata

0x924 .eh_frame_hdr

0x960 .eh_frame

0x200d98 .init_array

0x200da0 .fini_array

0x200da8 .dynamic

0x200f98 .got

0x201000 .data

0x201010 .bss

0x0 .comment

0x0 .symtab

0x0 .strtab

0x0 .shstrtab

Most of these aren’t relevant to us, but a few sections here are to be noted. The .text section contains the instructions (opcodes) that we’re after. The .data section should have strings and constants initialized at compile time. Finally, the .plt which is the Procedure Linkage Table and the .got, the Global Offset Table. If you’re unsure about what these mean, read up on the ELF format and its internals.

Since we know that the .text section has the opcodes, let’s disassemble the binary starting at that address.

# disas1.py

from elftools.elf.elffile import ELFFile

from capstone import *

with open('./bin.elf', 'rb') as f:

elf = ELFFile(f)

code = elf.get_section_by_name('.text')

ops = code.data()

addr = code['sh_addr']

md = Cs(CS_ARCH_X86, CS_MODE_64)

for i in md.disasm(ops, addr):

print(f'0x{i.address:x}:\t{i.mnemonic}\t{i.op_str}')

The code is fairly straightforward (I think). We should be seeing this, on running

› python disas1.py | less

0x6a0: xor ebp, ebp

0x6a2: mov r9, rdx

0x6a5: pop rsi

0x6a6: mov rdx, rsp

0x6a9: and rsp, 0xfffffffffffffff0

0x6ad: push rax

0x6ae: push rsp

0x6af: lea r8, [rip + 0x23a]

0x6b6: lea rcx, [rip + 0x1c3]

0x6bd: lea rdi, [rip + 0xe6]

**0x6c4: call qword ptr [rip + 0x200916]**

0x6ca: hlt

... snip ...

The line in bold is fairly interesting to us. The address at [rip + 0x200916] is equivalent to [0x6ca + 0x200916], which in turn evaluates to 0x200fe0. The first call being made to a function at 0x200fe0? What could this function be?

For this, we will have to look at relocations. Quoting linuxbase.org

Relocation is the process of connecting symbolic references with symbolic definitions. For example, when a program calls a function, the associated call instruction must transfer control to the proper destination address at execution. Relocatable files must have “relocation entries’’ which are necessary because they contain information that describes how to modify their section contents, thus allowing executable and shared object files to hold the right information for a process’s program image.

To try and find these relocation entries, we write a third script.

# relocations.py

import sys

from elftools.elf.elffile import ELFFile

from elftools.elf.relocation import RelocationSection

with open('./chall.elf', 'rb') as f:

e = ELFFile(f)

for section in e.iter_sections():

if isinstance(section, RelocationSection):

print(f'{section.name}:')

symbol_table = e.get_section(section['sh_link'])

for relocation in section.iter_relocations():

symbol = symbol_table.get_symbol(relocation['r_info_sym'])

addr = hex(relocation['r_offset'])

print(f'{symbol.name} {addr}')

Let’s run through this code real quick. We first loop through the sections, and check if it’s of the type RelocationSection. We then iterate through the relocations from the symbol table for each section. Finally, running this gives us

› python relocations.py

.rela.dyn:

0x200d98

0x200da0

0x201008

_ITM_deregisterTMCloneTable 0x200fd8

**__libc_start_main 0x200fe0**

__gmon_start__ 0x200fe8

_ITM_registerTMCloneTable 0x200ff0

__cxa_finalize 0x200ff8

stdin 0x201010

.rela.plt:

puts 0x200fb0

printf 0x200fb8

fgets 0x200fc0

strcmp 0x200fc8

malloc 0x200fd0

Remember the function call at 0x200fe0 from earlier? Yep, so that was a call to the well known __libc_start_main. Again, according to linuxbase.org

The

__libc_start_main()function shall perform any necessary initialization of the execution environment, call the main function with appropriate arguments, and handle the return frommain(). If themain()function returns, the return value shall be passed to theexit()function.

And its definition is like so

int __libc_start_main(int *(main) (int, char * *, char * *),

int argc, char * * ubp_av,

void (*init) (void),

void (*fini) (void),

void (*rtld_fini) (void),

void (* stack_end));

Looking back at our disassembly

0x6a0: xor ebp, ebp

0x6a2: mov r9, rdx

0x6a5: pop rsi

0x6a6: mov rdx, rsp

0x6a9: and rsp, 0xfffffffffffffff0

0x6ad: push rax

0x6ae: push rsp

0x6af: lea r8, [rip + 0x23a]

0x6b6: lea rcx, [rip + 0x1c3]

**0x6bd: lea rdi, [rip + 0xe6]**

0x6c4: call qword ptr [rip + 0x200916]

0x6ca: hlt

... snip ...

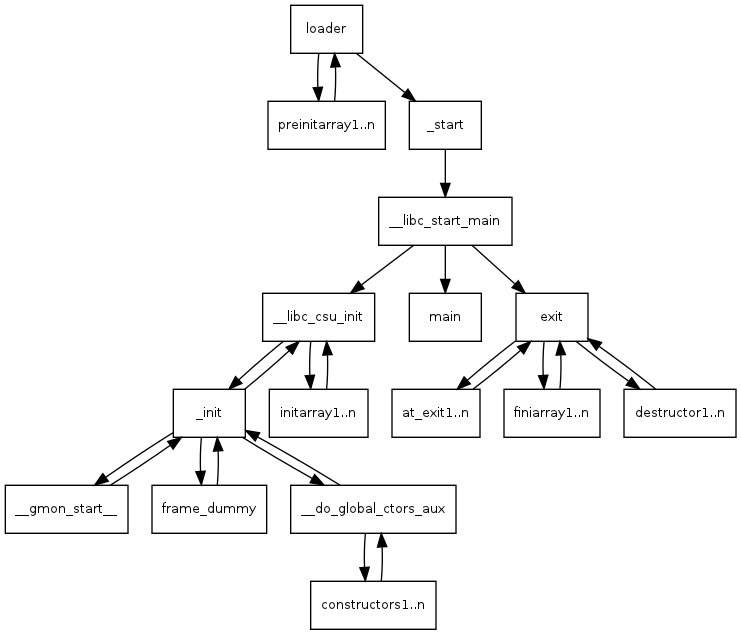

but this time, at the lea or Load Effective Address instruction, which loads some address [rip + 0xe6] into the rdi register. [rip + 0xe6] evaluates to 0x7aa which happens to be the address of our main() function! How do I know that? Because __libc_start_main(), after doing whatever it does, eventually jumps to the function at rdi, which is generally the main() function. It looks something like this

To see the disassembly of main, seek to 0x7aa in the output of the script we’d written earlier (disas1.py).

From what we discovered earlier, each call instruction points to some function which we can see from the relocation entries. So following each call into their relocations gives us this

printf 0x650

fgets 0x660

strcmp 0x670

malloc 0x680

Putting all this together, things start falling into place. Let me highlight the key sections of the disassembly here. It’s pretty self-explanatory.

0x7b2: mov edi, 0xa ; 10

0x7b7: call 0x680 ; malloc

The loop to populate the *pw string

0x7d0: mov eax, dword ptr [rbp - 0x14]

0x7d3: cdqe

0x7d5: lea rdx, [rax - 1]

0x7d9: mov rax, qword ptr [rbp - 0x10]

0x7dd: add rax, rdx

0x7e0: movzx eax, byte ptr [rax]

0x7e3: lea ecx, [rax + 1]

0x7e6: mov eax, dword ptr [rbp - 0x14]

0x7e9: movsxd rdx, eax

0x7ec: mov rax, qword ptr [rbp - 0x10]

0x7f0: add rax, rdx

0x7f3: mov edx, ecx

0x7f5: mov byte ptr [rax], dl

0x7f7: add dword ptr [rbp - 0x14], 1

0x7fb: cmp dword ptr [rbp - 0x14], 8

0x7ff: jle 0x7d0

And this looks like our strcmp()

0x843: mov rdx, qword ptr [rbp - 0x10] ; *in

0x847: mov rax, qword ptr [rbp - 8] ; *pw

0x84b: mov rsi, rdx

0x84e: mov rdi, rax

0x851: call 0x670 ; strcmp

0x856: test eax, eax ; is = 0?

0x858: jne 0x868 ; no? jump to 0x868

0x85a: lea rdi, [rip + 0xae] ; "haha yes!"

0x861: call 0x640 ; puts

0x866: jmp 0x874

0x868: lea rdi, [rip + 0xaa] ; "nah dude"

0x86f: call 0x640 ; puts

I’m not sure why it uses puts here? I might be missing something; perhaps printf calls puts. I could be wrong. I also confirmed with radare2 that those locations are actually the strings “haha yes!” and “nah dude”.

Update: It’s because of compiler optimization. A printf() (in this case) is seen as a bit overkill, and hence gets simplified to a puts().

Conclusion

Wew, that took quite some time. But we’re done. If you’re a beginner, you might find this extremely confusing, or probably didn’t even understand what was going on. And that’s okay. Building an intuition for reading and grokking disassembly comes with practice. I’m no good at it either.

All the code used in this post is here: https://github.com/icyphox/asdf/tree/master/reversing-elf

Ciao for now, and I’ll see ya in #2 of this series — PE binaries. Whenever that is.

Questions or comments? Open an issue at this repo, or send a plain-text email to x@icyphox.sh.